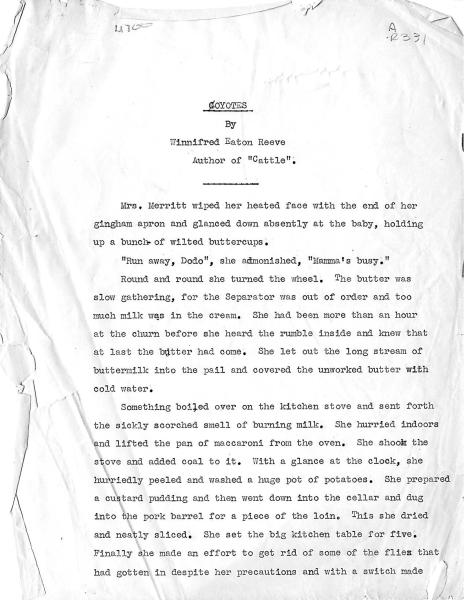

Coyotes

Mrs. Merritt wiped her heated face with the end of her gingham apron and glanced down absently at the baby, holding up a bunch of wilted buttercups.

“Run away, Dodo,” she admonished, “Mamma’s busy.”

Round and round she turned the wheel. The butter was slow gathering, for the Separator was out of order and too much milk was in the cream. She had been more than an hour at the churn before she heard the rumble inside and knew that at last the butter had come. She let out the long stream of buttermilk into the pail and covered the unworked butter with cold water.

Something boiled over on the kitchen stove and sent forth the sickly scorched smell of burning milk. She hurried indoors and lifted the pan of maccaroni from the oven. She shook the stove and added coal to it. With a glance at the clock, she hurriedly peeled and washed a huge pot of potatoes. She prepared a custard pudding and then went down into the cellar and dug into the pork barrel for a piece of the loin. This she dried and neatly sliced. She set the big kitchen table for five. Finally she made an effort to get rid of some of the flies that had gotten in despite her precautions and with a switch made

2 from long strips of paper attached to an old broom stick she beat the walls and the air and slapped at the screen door.

On the verandah where she had lately churned, she paused a moment to look out absently toward the hay fields, where even from the ranchhouse she could see the great golden piles growing under the skilled hands of her husband and son. In the adjoining field, the earth was black and rich, and spread over an expanse of one hundred smooth level acres, where the new “hand” summer fallowed.

The light of the Alberta day had slowly deepened and the blue skies had imperceptibly darkened. The first shadows of the slowly creeping evening were spreading in faint streaks across the sky. An intense, brooding silence seemed to hold the ending day as in a spell.

On all sides the immense grain lands lay like a wide stretching sea, whose billowing waves merged into the slumberous sky itself. One seemed to be on the top of a dim gold world. No sound! No stir! Life seemed suspended, inanimate, and a pervasive loneliness was over all.

Then in the utter stillness of the quiet deepening evening, arose out of the far bog lands, beyond the grain fields, the long wild wail of a coyote. It grew from a low moan of haunting appeal into a wild ascending note that floated out across the silent prairie land. Something almost human in its tone, something uncannily mystic and ghostly caused the farmer’s wife, well used to the coyote’s cry, to shiver slightly

3 as she turned back to the house.

At the kitchen door, and while the coyote’s cry was still reverberating across the prairie, she was seized with a sudden overwhelming premonition.

In her absorption in her work, she had forgotten Dodo. It was more than an hour since she had last seen the child going down the lane that divided the grain fields.

She called the baby’s name aloud, her shrill voice echoing back strangely from the cluster of brightly painted red and white buildings that were about a hundred feet from the ranchhouse. A sickening apprehension of she knew not what tore at the mother’s heart. As she ran from the house to the barn she called:

“Dodo! Dodo! Do – do-o-o-o-!”

The barn was empty of stock, for the work and saddle horses were all in the field and the milk cows had not yet been driven to the cow shed. A number of hens were clucking busily in the horse stalls.

The mother ran through the main barn and into the cowshed. She peered into the saddle room and the oat bin and she ran from stall to stall. She climbed to the hay loft and searched everywhere for her baby, and all the time she called her by name. From the hay loft window she scanned the barnyard, and coming down from the loft she went from building to building. The implement house, stripped for the summer’s work, the blacksmith shop, the granaries, the tool house, the piggery, the chicken houses, the well house – from one to the other sped the frantic woman, and then back to the ranchhouse, around it on all sides

4 and into the house and up and down the stairs and through every room and closet and even cellar upon the place. And back to the kitchen:

“Oh God!” she cried aloud.

The clock pointed to 5.30 o’clock. She had but half an hour in which to prepare the meal for the field hands, but she had forgotten their very existence.

In the middle of the barnyard she spun around in a distracted circle and began to scream, wild, agonizing, animal outcries. Waving her arms she sped across the barnyard, down the cowlane, on either side of which the four lines of barbed wire fencing protected the grain lands. At the end of the lane she came out into the pasture lands, and here horses and colts scampered before her. She ran hither and thither, dropping down into coolies and circling the edges of a small slough, from whose muddy surface arose hundred of mallard duck and mud hens.

On and on ran the woman. Flat on her stomach she crawled under a barbed wire fencing, nor cared not that an outjutting point tore the flesh from her arm. Through the oats thick as a forest and taller than a man the woman plunged. On and on, for half a mile, till she reached the end of the oats field and crawled again under barbed wire and came at last into the haylands.

The clank of the moving mower and the swish of the following rake sounded like the monstrous drone of a muffled engine, and clear across the prairie a man’s voice suddenly arose in song.

Her heart swelled in her breast. Her head began to reel,

5but she slackened not her pace. Following the long curved path of the mower she circled the field to meet the oncoming machine. Her dry lips moved soundlessly, her parched tongue seemed to choke her, her brow dripped with sweat. She stumbled as she ran over the rough stubble and the piles of new mown hay, but she recovered herself and quickened her speed.

Halfway across the hay field her husband saw her coming. Stolid son of the earth, unimaginative and unemotional, his wife’s sudden appearance in the hayfield, nevertheless brought a pucker to his brows. Mechanically the long whip cracked above the heads of the team and they pulled and strained upon the traces. With a loud crunch the mower came to a stop level with the stumbling woman.

Her breath was coming in great sobbing gasps. She shook her head from side to side, frantically, desperately, and her rough little hands tore at her lips that could no longer speak. In that terrible moment when she needed most her husband’s help speech had failed her. The shock had rendered her dumb.

“Why, mother, what has happened?”

Her lips moved, but the words came not. She clutched with shaking hands at his arm, her imploring eyes entreating his own.

Over a piece of rising ground came the following rake, and as it came, the song of the boy that rode it resounded beautifully in the quiet clear evening, but stopped suddenly as he saw his parents in the field. Less phlegmatic than his father, of an affectionate, impulsive nature, young

6 Donald leaped down instantly from the seat of the rake and hurried to his mother’s side.

“Why mom! What ails you? You ain’t hurt, are you mom?”

A guttural animal like moan was the only reply of the dumb woman. Than as the two men stared at each other, like a miracle, out of the utter stillness of the evening, again arose the long weird wailing of the coyote in the bog lands. As if the cry were a whip that lashed her lips into coherent utterance, at last she articulated:

“Baby! Lost!”

Her arm described a vague motion toward the north, and the farmer’s wife sank downward into darkness.

That night no less than fourteen searching parties spread out in a wide fanlike circle that covered nearly every inch of the land over a radius of five miles from the Merritt ranch. With lantern and gun, on horse and afoot, they searched the night through for the missing child.

To the south stretched for miles the grain lands, long roads and trail dividing the separate farms and here and there between a low slough or small lake.

East were grazing lands, this dry year overpastured. Half a municipality of open range, made up of hummocks and grey hills, rocky and bare. Sheep lands for the most part.

West were fine farms, both grain and cattle, and still farther west the land was wooded where it approached the foot-

7hills of the Rocky Mountains.

One approached the north lands warily, watching every step of the way, for beyond the outer layer of spending oat fields, began the heavy bog lands.

When the Alberta sun poured down its hot rays upon the prairie, then always it seemed that the north lands were especially inviting and desireable. Then they seemed to offer a cool retreat from the overheated fields. Thither the families of the farmers were accustomed to go a-picknicking, for on at least two sides of the green sloughs and quick sands were willow woods, and long lanes of birch and ash, and here the partridge and prairie chicken and the pheasant had their hidden coveys. The woods were full of berries, raspberry, gooseberry, saskatoon, wild cranberry, and chokeberries. The paths were carpeted with wild flowers, and the trees offered a paradise for the birds.

Children on their way home from school, riding over the roads and turnpike that the farmers had built over the marsh lands, would pause wistfully and longingly to gaze across into the depths of the unexplored and dangerous woods, unconsciously drawn by the sense of mystery and romance that seemed to hang about the place. But even the stoutest hearted of them heeded the warnings and admonitions of parents and teachers, to keep away from the bog lands, and in fact the place save in the special glens well known to the farmers, had become a sort of bugaboo in the popular imagination. Sometimes when late returning from school, or when the chill of a wet day brought clouds

8 of white steam and mist from out of the sloughs that crept toward the road like veritable wraiths, then the children would spur their tough surefooted

“broncs” along, and fled swiftly homeward as though pursued.

Sunny and smiling in the daytime, quite early in the evening white mists would curl up slowly out of the bogs and spread like smoke till before darkness had fallen all of the northland would disappear behind a veil of fog. Then from out the enveloping fog, with the darkness closing in on all sides, would arise that single, low, long wail, answered presently by its own weird echoes and the chorus of the coyote brethren.

Many were the tales told of the bog lands, and he who told not what his eyes and ears had seen and heard, repeated the tale of another. Always in those tales the unearthly cry was heard, the blaze and fury of fire-eyes, long white fangs and jaws dripping with gore – these were seen in the ghostly night. Endless were the legends of the travellers who had lost their way in the marsh lands. Some told of a white lady who floated over the bogs, with a great pack at her heels, and she it was who turned to mist and flung her veil forth to blind those who might pass. Hers, so they waid was the first voice of the night.

It was in the black sough in the very heart of the bog lands, that they had found Lilla, wife of Axel Swenstrom, and whether those black marks upon her white neck were made by the fangs of the ghostly pack or as some averred were from the thick fingers that had choked her to death none could say, and long since Axel had disappeared. People gave his shack a wide berth, and it was one of the first of the farms listed with the

9 War Veterans bureau.

The place had been “taken up” by Jake Watson immediately after he had returned from France. It was eight miles from the Merritt farm, and to reach it one was obliged to pass over a winding trail that zigzagged through woods and fields and skirted the far and treacherous edges of the marsh and bog lands.

Jake had no wounds to show for his four years service at the front, no medals and no pensions. The farm, nevertheless, represented the “gift” of a grateful government, and Jake’s six months pay gratuity went to pay the first installment on a twenty year loan for implements and stock.

Jake was well satisfied with his farm. Its isolation and quietness gave it an especial value to the soldier. Here at least the German guns could never reach. Here the incessant pounding of the four terrible years would not be heard save in sleep or delusion.

He was said to be

“queer,” and some declared that Jake was

“cracked.” Bud Morris, for instance, son of the wealthiest farmer in the country. Bud had been exempted from military service because of two missing toes from his left foot, and he had spent a night in the veteran’s shack. Bud persisted in the statement that the veteran was

“crazy as a bed bug” – though he was careful to make such statement out of sight and hearing of Jake Watson. The latter, so Bud declared, slept without covers upon his bed, even in winter, his dogs – six or seven of them, lying across him, and giving not only the necessary warmth, but a protective armor against all possible

10 attack. There were one thousand and one different methods of assault in the night against which a man had to be prepared had asserted the veteran to the plump Bud, whose pimpled face had turned a pasty color as Jake enlarged upon the subject, and then had gotten into his bed, pulled his

“cover” of dogs over him and left the farmer’s son to look out for himself on the bare floor of the shack. Jake was neither malicious nor cruel, but he had a clear memory, and that memory recalled to him the fact that during the four years when he (Jake) had slept in mud holes or any place wherein he could crawl, Bud had had his feather bed at home. How the tables were turned.

At this time the war was still near enough to the public heart and conscience that we had not reached the stage where we scowled at the word

“veteran” and avowed that they

“needn’t think were goin’ to support them in idleness for the rest of their days.” etc. Women still occasionally knitted sweaters and socks for the returned men, and a place was made for them at the farmer’s table. It was a matter of irritation that the government was placing them here there and everywhere among the farmers – that is to say, they were allowing them homesteads in parts of the country where previously one had had good open range, on which to run ones cattle freely. Now the range was being fenced and cut up and veteran’s shacks were going up on all parts of the prairie. Of course, there was consolation and remuneration also in the advent of the veterans among the farmers, for every one who had a bit of poor land or a farm that was known to be unremunerative listed it with the Soldiers Settlement Board and

11 in more cases than not was able to dispose of it to the soldiers. Certainly no one but a soldier would have bought the Swenstrom place of evil repute.

Jake took his time about arising in the morning. There were few chores to do. He had whittled his days down to an almost scientific minimum of labor. Prior to the war Jake had been an excellent farm hand, whose services were in demand by all the farmers of the district. Since his return his aversion to work had lost him more than one friend, and earned him such terms as “worthless,” “lazy,” and “goodfornothing.” Howbeit, Jake had returned with a vast loathing for exertion or labor of any sort or kind. He had one great desire – to lie out in the sun with his dogs and arise only when it was necessary to eat. Occasionally he suffered from moods of activity when he chopped wood, broke a bit of land, put in a crop of oats, and even cut some hay. Rather than milk the cow, with which the aforesaid grateful government had provided him, Jake had preferred to “tickle the tin” – an Alberta expression for using canned milk. He subsisted to a large extent upon game and the woods supplied him with ample food for both himself and his dogs.

Jake had a rheumatic left knee that was an infallible weather prophet. He could tell by the kind and extent of his twinges exactly what the weather was due to be like on the following day.

It so happened that on the night when half the county

12 was being scoured for the missing Merritt child, Jake’s left knee was especially troublesome, so that in spite of painkiller, and rum, it had kept him awake a good part of the night, and toward morning was especially troublesome. At five, therefore, in the morning, Jake sat up in his bed, surrounded by his dogs and expressed himself in language that was profane and impure. Having relieved himself after his fashion, and still rubbing the throbbing knee, Jake addressed himself to his

“family.”“Fellows,” said Jake, “it’s getting ready to pour down cats and dogs, and it looks to me as if we’d better be gittin’ busy and pull in some wood and eats before we get swamped in.”

His family replied with various thumpings of tails upon the floor, with leaping up to lick his face and to paw the soldier generally.

“That’ll do! That’ll do,” he admonished. “Git down, Ypres! Here you, Nervy Shapelle!” All of Jake’s dogs were named after some war famous part of France. “Git on down, I say! We gotta git on out and git some of them mallard duck that’s thick as thieves on the top of the slough. They’re waitin’ for us! Come along and we’ll have a hell-fine breakfast.”

He yawned and stretched himself, gave a final squeeze to his knee, put on his trousers – the only garment he discarded upon retiring – took down his rifle, and with his dogs at his heels, Jake opened his door. Instantly a united menacing growl burst from the throats of his dogs, as with a concerted motion they leaped forward on the run, and then held back, growling and barking.

On a mound that rose directly in front of the veteran’s

13 shack was a strange sight. Grouped in a circle about some object on the ground was a dozen or more coyotes, their noses turned to the earth. The growls of the dogs brought their noses skyward, and sent forth the long mournful wail in response.

“What the blazes they got under there?”

Jake’s rifle came to his shoulder, but some impulse held him back from firing at the group, and the shot went upward into the air. The sharp pop of the rifle sufficed. Instantly there was a scattering of the pack. The startled coyotes leaped into the air, sprang this way and sprang off that way, retreated to the wood and the bush and hovered within the edge of it, awaiting the opportunity to return to their prey. The veteran had run swiftly forward, and as he ran he fired two more shots into the bush, sending the coyotes into final retreat.

The child lay upon her side, her bright curls were dam and scattered in matted disorder across her smudged and tearstained face. One little hand still tightly grasped the lard pail in which were a few of the

“fowers” she had picked for her mother, the other was tucked under her cheek, as she would have put it had she been asleep in her little cot at home. Briars and thorns had scratched her hands and face; leaves were in her hair, and her feet and dress were sopping wet where she had trudged through some marsh, but beyond these casualties the child was unhurt. She was sound asleep. As Jake lifted her

14 in his arms, she opened a pair of bluebell eyes and said:

“Nice yellow dog carry Dodo.”

You can hear various versions of the Dodo story. Some say that no child could have walked eight miles in a night, and to reach Jake Watson’s shack she would have had to pass through the bog lands unless she had gone around the long trail, which would have doubled the mileage. How then did she arrive at the front of the shack had not the coyotes carried her? The answer to this, by those who are inclined to scout the tale is that “the poor little thing didn’t know what she was talking about. Probability is Jake found her nearer her home than he likes to make out.” If that were true, replies the other side, what of the searching parties? Were they not on all sides of the marsh on that night?

Bert Bowers, old-timer and something of an oracle among the farmers of the district, says, chewing upon the tobacco in his left cheek and speaking out of the corner of his mouth:

“Psha! You can’t tell me nothin’ about coyotes. They are the meanest critters that ever run on four legs. You can’t tell me that coyotes would leave a little tyke like that alone. Psha! I guess I know coyotes. I wish I had a dollar for everyone I’ve shot.”

“Then you think Jake and the kid made it all up?”

“No, I don’t say nothing of the sort, and you needn’t take the words out of my mouth. Its like this. Coyotes are powerful sneaks. They don’t touch nothings thats alive or stirrin’ but they’ll foller and foller and foller till you drop, and 15then look out!”

“But she did drop,” argues a persistent one. “She was on the ground when Jake found her.”

The oracle screws his eyes and squints off appraisingly:

“If Jake hadn’t come along at exactly that moment, I betchu anything I got that kid wouldn’t been alive today.”

Farmer Merritt himself, grave and stern, his hair grizzled grey since the night in the bogs, puts out his jaw stubbornly:

“I don’t know anything about coyotes, but I ain’t going to stand by and let no man say one word against my neighbor, Jake Watson. He’s a man!”

Mrs. Merritt, whose high cheek bones have recovered their color, and whose tongue fails her not now, smiles around the circle:

“Talking of Jake! We all got exempted because we was raisin’ crops, so didn’t have to go across the water to fight the Germans as Jake did. If we didn’t get exempted because we was farmers, then we had squint eyes or flatfeet. When Jake went down to enlist at first they told him his feet were flat as pancakes and that he wouldn’t be no good fighting Germans, but he kept at them and he kept at them, and he got took, and no one thought anything more about his flat feet when he was chasin’ after Germans, and neither did them same feet bother Jake when he was trampin’ ten miles through the marshlands, with the rain just pounding down upon him, and that baby wrapped up snug in his old army coat and himself soaked to the bone.”

16

A long silence greets this eloquent outpouring from the farmer’s wife, and there is an uncomfortable shifting of feet and hands. Then someone says:

“Psha! Mrs. Merritt, don’t get so hot under the collar. We ain’t saying nothing against Jake. We all was talkin’ about coyotes!”